Welcome to Christopher Priest’s perspective on the very early days of Milford in the UK.

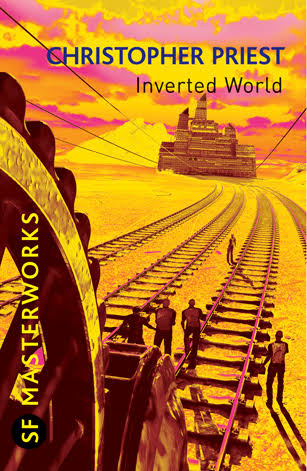

Christopher Priest: Inverted World. Workshopped at Milford 1972 in its original novella format.

The first Milford Conference in the UK was held in October 1972, in a small hotel called the Lydgate, in the Hampshire town of Milford-on-Sea. I have been reminded of these facts (and a few others) by the Milford website, where there is a year-by-year write-up.

I enjoyed the Milfords I went to, and I attended several during the 1970s, but thinking back I realize that at first things went badly for me. It’s traditional to emphasize how much can be gained and learned from a week closeted away with your writing colleagues, not to mention what fun can be had at Milford (all of which is true), but I think it’s perhaps only fair, and certainly a bit more interesting, to describe some of the dangers.

At the first UK Milford I met and became friendly with the SF writer Richard Cowper. When he died suddenly some three decades later, I felt moved to write a memoir of our first meeting. Because it also contains a frank description of what happened at that first Milford UK I think it’s worth reproducing here. Names are mentioned, not always favourably. One of the real qualities of a Milford workshop is the freedom to speak candidly, knowing that there is what lawyers call parity of arms: you can speak your mind without fear or favour. Writing this account I felt it would be against the spirit of Milford to try to disguise identities, so here they are, warts and all.

I gave it the title A Meeting with Richard Cowper:

*

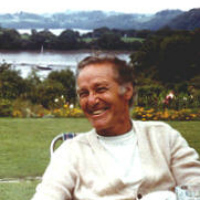

I knew him by his real name, John Murry. He was born John Middleton Murry, the same name as his father, the influential critic, essayist and pacifist. Later I heard him addressed as ‘Colin’, another name he wrote under: this was the Colin Murry who had published four general novels in the 1950s and 1960s. Some of John’s family still called him by his boyhood nickname ‘Col’, or even ‘Carl’. I once asked him what name he liked to be called by, and he just laughed and said he’d answer to almost anything so long as it wasn’t obviously rude. To most people in the world of science fiction, and in particular to those fellow writers who went to the Milford Conferences with him during the 1970s, he was Richard Cowper, or Richard.

John Middleton Murry – alias Richard Cowper

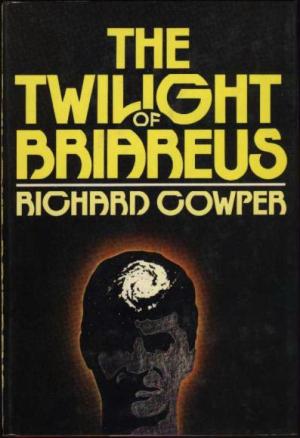

My friendship with him did not start auspiciously. In the summer of 1971 I was asked for an opinion on a manuscript by the publishers Victor Gollancz – it was Cowper’s novel The Twilight of Briareus. By the time I’d finished it I was a Cowper convert. I thought there were one or two minor things that needed fixing, but nothing for anyone to worry about. It was a smashing novel: a fresh take on the ‘disaster’ story, with many good satirical touches. I wrote an enthusiastic reader’s report to recommend it and assumed Gollancz would publish it some time in the next year or so.

About ten months later I was looking forward to taking part in the first British Milford writers’ workshop. One morning I received a phone call from James Blish’s wife, Judy, who was organizing everything. She told me that numbers were a little lower than expected and that there was room for a couple more people. Did I know of any other writers who might be able to come? Richard Cowper was the first and only writer I thought of. I had kept a note of his address from the manuscript I’d read, so I passed it on to her. A month or so later Judy Blish circulated the list of attendees and there was Richard Cowper’s name on the list. I was pleased my recommendation had been taken up and I looked forward to meeting him.

So we all went to Milford in September 1972. The scene needs to be set, because it had a bearing on what was to follow.

Fifteen writers took part, which meant that over the course of the next three days we had to read and discuss five manuscripts a day. Anyone who has taken part in such a workshop will realize what a heavy commitment that was, involving hours of intensive reading. The hotel was a small one, with the lounge chosen for the workshop only just big enough to hold everyone. With our arrival at this place we started learning about The Rules.

The workshop was being introduced to Britain by the American writers who had been to the US Milford conferences, and they were running the show. In practice this meant James and Judy Blish, and the nominal chair of the workshop, Anne McCaffrey. They were keen on rules, these people.

The first rule, for instance, was that the manuscripts had to be placed in the workshop room from the start of the conference. No copies of any of the manuscripts must ever be removed from that room – e.g., they weren’t allowed to be taken to one’s own room for a quiet read – because that would make it difficult if someone else wanted to read it. Everything therefore had to be read in the main room in the company of everyone else. No manuscript must be discussed with any of your fellow professionals in advance of the workshop session, and this included a ban on making expressive noises – groans of disappointment, gnashing of teeth, hysterical laughter, and all that. Notes must be kept private. Silence must be maintained at all times so as not to break the concentration of people still reading. In the workshops themselves no one, but no one, must speak for more than three minutes. Judy Blish issued these directives in a voice of chill authority. In this she echoed the words of her husband. He too was strong on the rules, describing them as a formula that worked. The Blishes were clearly inflexible

But what was all this ‘fellow-professional’ stuff she kept going on about? Everyone else was in fact a professionally published writer, a precondition for being there, but she wasn’t. She had never sold a thing. For a while I assumed she was being allowed in because she had done the organizing, and would keep out of the way once the workshops began. As things turned out, she was to take part in all the workshop sessions – this was one of several of their own rules that the Blishes interpreted in different ways, depending on who you were. Later on, for instance, Brian Aldiss tried to get his children in so they could listen to his manuscript being discussed – this mild request led to a bad-tempered confrontation which was ‘resolved’ by the ludicrous compromise of making two intelligent teenagers sit behind a curtain while their celebrated father’s work was workshopped. Judy Blish, a non-writer, was apparently exempt from her own rules. It wouldn’t have mattered if she hadn’t made it matter.

Anyway, all that was ahead and did not directly involve me. I looked around at the others.

Many of them were already friends, or at least they were people I thought might become friends. In addition to the Blishes, and McCaffrey, the attendees were Mark Adlard, Brian Aldiss, John Brunner, Ken Bulmer, George Locke (who had published stories as ‘Gordon Walters’), John Phillifent (who was ‘John Rackham’), David Redd, Josephine Saxton, Andrew Stephenson, Peter Tate, myself and Richard Cowper. It was an interesting group to be in. While that first evening slowly passed, as the full import of the Blish Rules fell on us, what I really wanted to be doing was relaxing socially with the other writers, breaking the ice in the bar, complaining about publishers and agents, listening to stories about cheques not arriving when promised, and so on. Generally talking shop, in other words. Instead, La Blish instructed us that the sooner we began the silent reading of the manuscripts, the better.

I took all this timidly because I was glad to be at Milford and did not want to rock the boat. I was one of the youngest and most inexperienced writers there. I was daunted by the presence of well established writers like Brian Aldiss and John Brunner, and yes, even James Blish himself. Blish turned out to be a world-class bore, though – he dominated every workshop session, blatantly exceeding his own three-minute limit rule, endlessly (and repetitively) droning on about Henry James’s essays on viewpoint, and his own eccentric ideas about what he called said-bookisms. Everyone was as timid and polite about his behaviour as I was, but we all noticed and tried to conceal our yawns.

On that first evening we weren’t up to full strength because Richard Cowper hadn’t arrived. He had phoned ahead from somewhere: his car broke down on the way and he was going to be delayed. The hotel staff put out a cold supper for him, and we settled down to our reading.

Late in the evening, car headlight beams flashed across the windows from outside and a few minutes later a slim figure slipped past on his way to the hotel reception. It was our first glimpse of Richard Cowper. Anne McCaffrey went out to reception to greet him on our behalf.

The workshop sessions began in the afternoon of the next day. Because he had been late arriving, and therefore hadn’t had the same chance as everyone else to read the early manuscripts, Richard’s own submission was one of the first ones to be workshopped. It was an extract from Briareus (which incidentally made my own reading load a little lighter for the first day). When the piece was workshopped several people said how much they enjoyed it and that he should go ahead and complete the novel. When my turn came to comment on the manuscript I couldn’t resist revealing that I knew Cowper had already finished the book, and that it was every bit as enjoyable as everyone expected. While I was speaking, Richard was giving me a funny old look from across the room.

The workshop sessions began in the afternoon of the next day. Because he had been late arriving, and therefore hadn’t had the same chance as everyone else to read the early manuscripts, Richard’s own submission was one of the first ones to be workshopped. It was an extract from Briareus (which incidentally made my own reading load a little lighter for the first day). When the piece was workshopped several people said how much they enjoyed it and that he should go ahead and complete the novel. When my turn came to comment on the manuscript I couldn’t resist revealing that I knew Cowper had already finished the book, and that it was every bit as enjoyable as everyone expected. While I was speaking, Richard was giving me a funny old look from across the room.

Afterwards, during the short break before the next session, he came across to me. He asked how I had managed to read the whole manuscript, so I told him about Gollancz sending it to me. ‘Ah-hah!’ he cried. ‘Then it was you!’

‘Me?’

‘The man with the Golden Rule of Science Fiction. We meet at last! Ah-hah! Found you!’

He was grinning through all this so I didn’t take it too seriously, but it was obvious I’d somehow touched a raw nerve. We sat in the bar and had a couple of quick beers together. I told him I loved the novel and that with the exception of a couple of tiny things I had given it a wholehearted recommendation. I added that I was surprised that Gollancz hadn’t published it yet and had been expecting to see it announced at any moment.

‘Not on your nelly,’ he said. ‘The buggers turned it down flat. They claimed it broke the Golden Rule of Science Fiction. They sent me a copy of the report they’d had from their SF reader.’

‘What? I’ve never heard of that. If anyone said it, it wasn’t me. I don’t even know what the golden rule of science fiction is!’

‘Their reader said that golden rule of science fiction is that you mustn’t have two unbelievable things in the same story.’

It was news to me and I said so. I was amazed that there was even such a formulation, and I said that too. I immediately thought of half-a-dozen exceptions to the ‘rule’. One of the most obvious is of course John Wyndham’s The Day of the Triffids, a classic of SF by any definition, yet one which turns on two global catastrophes: sudden worldwide blindness, and the simultaneous emergence of deadly, walking plant hybrids.

We didn’t get too far with this conversation because Constable Blish was patrolling her beat, rounding up stragglers so we could get on with the next story. Richard and I blended back in with the rest of the workshop and no more was said about Briareus. However, I remained astonished by the news that Gollancz had rejected the novel. It was exactly the kind of SF Gollancz could do well with. They had always actively supported British writers. Also, skill showed on every page: the book was psychologically convincing, it was satirical, moving, worrying, occasionally funny and well told all the way through. Since when had this supposed ‘golden rule’ come into effect? It rather reminded me of the endless rules we were living by, down there in Milford-on-Sea.

Then came the next day and with it, for me, a full quota of manuscripts to plough through. One or two of them were huge, more than ten thousand words in length, and I found several of the stories pretty difficult to read or think about. One of the worst of these stories was the one put into the workshop by Anne McCaffrey.

It seemed incredible to me that a so-called professional writer (and by this time McCaffrey had become a big name, at least in the USA) could produce such amateurish and shoddy work. It was in general incompetently written, but even worse than that it was illogical and incomprehensible. It looked like something a new writer would draft then throw away while getting ready to start submitting work to magazines. I sat on the uncomfortable chair in a corner of the cramped lounge, trying to keep my mind on the dreadful story. I was constantly distracted by the presence of so many other people around me. Everyone was maintaining silence, but it was the sort of oppressive non-silence where you can hear whispering all the time, and there was constant movement as people fidgeted, or got up and walked about the room. I kept restarting the manuscript from the beginning, trying to make sense of it and keep my mind on it. Each time I tried I could only get about halfway down page two before either losing interest or having my attention distracted.

The deadline of the afternoon workshop session was approaching. Before breakfast that morning, while exploring the hotel, I’d come across a small TV lounge tucked away at the far end of one of the corridors. After my fifth attempt to get past page 2 of McCaffrey’s story I quietly stuffed the manuscript under my jacket and slipped out of the workshop room. I walked down to the TV lounge and went through the door. Already in the room, horizontal on a sofa, was Richard Cowper. He had an unfinished manuscript open across his chest and a cigarette smouldering in his fingers. He was staring at the ceiling.

The moment I saw him I backed away. ‘Sorry,’ I said. ‘I didn’t realize there was anyone in here.’

‘Come in, come in!’ he said, conspiratorially. ‘Come in and close the door and I’ll buy you a drink.’ I realized then that it was McCaffrey’s appalling manuscript he had been trying to read. As he sat up, he brandished it at me. ‘I can’t get past page two of this bloody story,’ he said. ‘What do you think of it?’

‘I’m on page two as well. It’s impossible to read, isn’t it?’

With these words, and because we had already ignored the ban on removing manuscripts, we had broken at least three of the Blish Rules and no doubt went on to break many of the rest.

Richard and I sat in the privacy of that tiny lounge for most of the morning. We found we had a lot to talk about. We were united by our enraged reaction to the McCaffrey manuscript, by the way its amateurish style and unsophisticated ideas were actually offensive in the context of discussion by other writers. What did Anne McCaffrey expect us to do with such poor work? It couldn’t be taken seriously as a piece of achieved writing, so did she want her fellow writers to correct her erratic spelling and dodgy grammar? Sort out her illogical plot for her? Explain how to tell a story? Teach her how to write?

We knew it was hopeless. Already, Ms McCaffrey had been laying down the law to us: she kept reminding us she was a Hugo and Nebula winner, and although her manner was theatrically friendly there was a kind of barrier in there. She liked telling people what to do but she didn’t seem to be much of a listener. I hadn’t really thought about it until then, but Richard, giggling and exclaiming and groaning amusingly, put everything in context. We sat in that tiny room for another hour, occasionally sneaking out to the bar to replenish our glasses, the copies of the awful manuscript lying unread on the floor between us.

‘By the way,’ he said, as lunchtime approached. ‘Do you see anything wrong with my eyes?’

‘Eh?’

‘The other night, when I arrived late, I was just signing the guest book in reception, when this woman I’d never seen before in my life came rushing up to me. Scared me out of my wits! She grabbed me by the shoulders and stared straight into my face. ‘You have the eyes of a prune!’ she yelled, then she kissed me.’

‘A prune?’ I said.

‘Her very words! It was Anne McCaffrey. I tell you, mate, at that moment I nearly ran back to my car and fled.’

Later, feeling much jollier and amused by all the nonsense, we returned to the main room, sat in our respective corners, ground our way mutely through the unintelligible McCaffrey manuscript. We must each have finally found something to say about it that wasn’t completely rude, and the next day the workshop finished and we all went home.

The eyes of a prune? It was inexplicable and ridiculous, but it helped launch what turned out to be a thirty-year friendship. [2002]

*

After this article first appeared in a fanzine I received an amused letter from Malcolm Edwards, then running the Victor Gollancz SF list. He had gone back through the firm’s files from thirty years before and discovered that my version of Gollancz turning down Briareus couldn’t have happened quite as I describe it here. There was a problem with dates, the order in which things happened. On reflection, I realized that I was unconsciously concatenating two conversations with Richard Cowper.

Gollancz did of course publish Briareus the year after the first Milford Conference, as well as many more of Richard’s books. The misbehaviour of those middle-aged writers at Milford was in fact more or less as described, although I did leave out the bit where one of the most famous writers stormed out in a rage, where two others went for a midnight swim but afterwards couldn’t remember where they’d left their clothes … and when someone suddenly appeared at dinner dressed only in a black plastic bin-liner. No, that was another year.

Malcolm Edwards also solved the mystery of ‘eyes of a prune’. It seems likely that what Anne McCaffrey said was, ‘You have the eyes of Athune,’ which is the name of a character from one of her novels about dragons. If so, this bit of tunnel vision, in which a writer of a few fantasy novels assumes the whole world has read and memorized every word, is not nearly as ludicrous as saying ‘prune’, but a bit more revealing.

*

I decided against going to Milford the following year. I can no longer remember why: possibly I was short of money, or other things were happening. I lacked incentive, too. I had not really enjoyed the first. The 1973 conference took place in a hotel in Barton-on-Sea, just along the coast from Milford itself. I did travel down to the party on the last evening. I picked up the feeling from the people who had been there that because of the poor quality of the hotel the week had not been a great success.

However, I decided to try again in 1974. This was the first year at the Compton Hotel in Milford itself, the venue for several more years to come. The Blishes were there again, parroting their rules, as was Anne McCaffrey. Richard Cowper had also missed 1973 but like me was back, and present too were Samuel R. Delany, Robert Holdstock, Peter Nicholls, Dan Morgan, Josephine Saxton and several more. The workshops were more varied than before, and much of the criticism was harder-edged, and therefore stimulating and useful. Three minutes on the receiving end of Chip Delany’s acute and witty criticism could change your whole approach to writing. However, James Blish was there to lower the temperature once again by informing us several times about the rules of viewpoint and said-bookisms.

I returned for more Milfords throughout that decade, with my final one (at least for the time being) at the Compton in 1980. Apart from the general stimulation of the gestalt experience of a closed workshop environment, what benefit was there? What did I learn?

It’s impossible to say what Milford does for one’s own writing, because (as Al Reynolds has said on this blog) when you get home afterwards you have to measure carefully the importance and relevance of what people have said about your work. You can learn from it, but you have to learn also what not to accept. And anyway, as working writers our general growth and self-awareness is a complex and subtle procedure, which is almost impossible to analyse or understand. Everyone learns and develops as a writer throughout their working lifetime, and a workshop eventually becomes merely a part of that process.

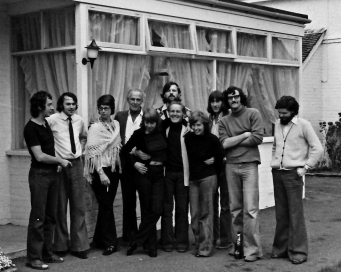

Milford 1976 (back row) l-r: David Garnett, David Redd, Judy Blish, Jerry Schutz, Andrew Stephenson, Christopher Priest, Robert Holdstock, Duncan Lunan. (front row) l-r: Charlotte Franke, Richard Cowper, Pamela Bulmer

But I learned a couple of things about workshops that might be useful to know.

The first came from a bad experience of my own. In 1978 I took a manuscript with the working title Schubert’s Eighth. This faux title was a hint. The story was unfinished, a work in progress, a Dream Archipelago story set on a tropical island, a sweltering place of remittance men and idlers and sexual misbehaviour. In fact, I was working on it right up until the day before Milford began. I added a note to this effect, and saying that I had no idea how the story would end. This was because almost everything I have ever written has not found its ending until I reach the point. But I was soon to regret this note. During the workshop one person after another gave me their ideas about how the story could end. Every word of what they said was to me irrelevant. I barely listened. This is not arrogance: my story was a work in progress, with a conclusion somewhere ahead which would develop organically from the characters, the events, the mood, and much else.

After the workshop, one of the people who had spoken in the greatest detail about a possible ending came up to me and asked what I thought of his ideas. I told him frankly I was still working through the story, and that what other people thought about plot development hadn’t been of much interest. He became insistent, saying that ‘his’ ending would vastly improve the story. Obviously, I couldn’t agree with that, but all this was in the generally constructive context of a Milford workshop, and so we did not argue. But that evening, when everyone else was relaxing downstairs, this guy was nowhere to be seen. Whenever there was free time during the rest of the week he remained out of sight.

On the last day he walked up to me, thrust a bundle of papers into my hand, and said, ‘There! I’ve finished the story for you!’ I glanced at it aghast. His handwriting had been scribbled all over the copy of my manuscript: between the lines, along the margins, but mostly on the blank rear pages.

I glimpsed enough of it to see that my tropical island saga of sweaty bodies and naughty doings had been replaced by some kind of Cold War thriller. Schubert’s unfinished symphony (to which I had jokingly referred) was a masterpiece – my story had been turned into a travesty.

Back at home, I realized miserably that I could never now complete that story. I felt it had been stolen from me, transformed, buggered about with. I abandoned all hope for it. But then, a month or so later, the anthology editor to whom I had promised a story (that very one) phoned me to ask when I was going to send it in. Horror!

I told him what had happened, that the story was now unfinishable, and that as a more general result of this experience I had no confidence in starting something new. He said that the cover of the anthology had been designed and distributed, and my name was on it. My name had already been used in pre-publicity. In short, I had to send him something. To cut a long and painful story short, with deep reluctance I went through the ‘revised’ manuscript, polished what I could of it, tried to repair the damage done to it … and sent it in. It is a terrible story, the worst thing ever published under my name, and I have never forgiven the person involved.

From this anecdotal horror story I hope you will realize that you should never put into a workshop a manuscript that is still a live project. And if you are presented with such a manuscript in a workshop never, ever, try to propose revisions or developments … unless the writer has explicitly requested that sort of input.

The other thing I learned from Milford is more positive. Some participants turn up at the workshop with ‘problem’ manuscripts – work they have struggled to complete, or something they haven’t been able to get quite right, or a story that has never been sold. You can quickly see the temptation of this. I think that was Anne McCaffrey’s explanation for the dreadful thing she took to the first Milford. I feel pretty certain that at least one of my own Milford MSS would have fallen into this category, and I know for certain there have been others brought to the workshops.

However, as many other people have done, I usually put in MSS which I considered to be the best I could do, work which (wrongly or rightly) I was willing to be judged by as a writer. Workshop feedback on stories like this is inexpressibly valuable. Of course, sometimes your ambition is given a cold shower of reality, but in general the quality of the workshop discussion rises perceptibly. Much that is useful, negative as well as positive, is said. This is also something you feel when you read someone else’s best work. You find yourself communicating with your fellow writers on a high level, with valuable insights coming from all sides. I’m sure, for example, that most of the Milfordites who were present on the day will still remember the workshop discussion of Richard Cowper’s marvellous novella, The Custodians. A sense of thrill gripped us all as we realized the exceptional quality of the work we were discussing.

However, as many other people have done, I usually put in MSS which I considered to be the best I could do, work which (wrongly or rightly) I was willing to be judged by as a writer. Workshop feedback on stories like this is inexpressibly valuable. Of course, sometimes your ambition is given a cold shower of reality, but in general the quality of the workshop discussion rises perceptibly. Much that is useful, negative as well as positive, is said. This is also something you feel when you read someone else’s best work. You find yourself communicating with your fellow writers on a high level, with valuable insights coming from all sides. I’m sure, for example, that most of the Milfordites who were present on the day will still remember the workshop discussion of Richard Cowper’s marvellous novella, The Custodians. A sense of thrill gripped us all as we realized the exceptional quality of the work we were discussing.

So – always aim as high as possible when entering work. Submit something recent, something finished, something you think is as good as you can get, at least for now. A Milford workshop is a classic example of something where if the best goes into it, the best comes out.

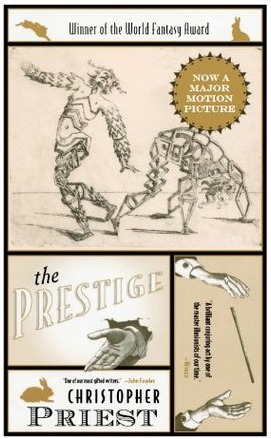

Christopher Priest is a British novelist and science fiction writer. His works include Fugue for a Darkening Island, Inverted World, The Affirmation, The Glamour, The Prestige and The Separation.

Christopher Priest is a British novelist and science fiction writer. His works include Fugue for a Darkening Island, Inverted World, The Affirmation, The Glamour, The Prestige and The Separation.

In 1983 Priest was named one of the 20 Granta Best of Young British Novelists. In 1988 he won the Kurd-Laßwitz-Preis for The Glamour as Best Foreign Fiction Book. Amongst many other awards he has won the BSFA award for the best novel four times, the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for Fiction and the World Fantasy Award (for The Prestige). He has been nominated for Hugo Awards in the categories of Best Novel, Best Novella, Best Novelette, and Best Non-Fiction Book, and was guest of honour at the 63rd World Science Fiction Convention in 2005.

Pingback: Pixel Scroll 10/11/16 When An Unscrollable Pixel Meets An Irretickable File | File 770